The fifth child born to Thomas and Mary Ann Holt (nee Edwards), Elizabeth Maud Holt came into the world on 13 July 1862 in Easenhall in Warwickshire, England. Her father, Thomas, worked as an agricultural labourer while her mother (in her youth) was a ribbon weaver.

The family tended to live in small towns surrounding the larger market town of Rugby and, as Elizabeth grew, she was joined by three more siblings.

Unfortunately not much is known about her early years in Warwickshire. Her family was not wealthy so it’s likely they lived in small cottages.

This can be seen in the 1871 English Census taken on 2 April. Elizabeth (aged 8) was listed in the Census with her parents and three younger siblings. They were living in a cottage in the town of Bilton in Warwickshire.

Elizabeth was the only child who was recorded as a ‘scholar’ though it’s likely her brother, Thomas also went to school. The Holt family, like so many other working class families, benefited from The Elementary Education Act passed in 1870. It provided for the education of all children between the ages of five and thirteen. Elizabeth may have first started school in the previous year at the age of seven.

Elizabeth was the only child who was recorded as a ‘scholar’ though it’s likely her brother, Thomas also went to school. The Holt family, like so many other working class families, benefited from The Elementary Education Act passed in 1870. It provided for the education of all children between the ages of five and thirteen. Elizabeth may have first started school in the previous year at the age of seven.

Schooling in the 1870s would have included the three R’s – reading, writing and arithmetic along with religious instruction. Children learnt their lessons simply by copying into their books what the teacher had written on the blackboard.

Along with lessons at school, there would have been lessons and work at home, perhaps in the form of cleaning, cooking and sewing.

Elizabeth may have only been attending school for a couple of years when her family was rocked by tragedy. In early January 1873, Thomas Holt passed away at the relatively young age of 43. The Holt family lost their husband, father and the main source of their income.

While it’s possible Elizabeth continued her schooling (she was nine at the time and would have had about three more years left) it’s also likely she was forced to help her family in some way, perhaps by obtaining employment. Despite the Education Act, many children were kept out of school if earning an income was more important.

Certainly by the age of 13 (when school officially ended for the working class) she was at work as a domestic servant. Though it’s not been verified, a story told to me by my Great Aunt states that Elizabeth was employed by a family in England to help care for their children.

From 1875 to 1877 Elizabeth most likely resided with a wealthier family in England (possibly somewhere in Warwickshire) and was required to do all the household chores such as cleaning, washing dishes, ironing and mending. She worked for most of the day, seven days a week. There may have been the occasional afternoon off but there was no such thing as a weekend. She was paid, but given the early death of her father, much of that income may have been sent back to her mother and siblings.

In Western Australia during the 1870s, wealthy families were crying out for well-trained domestic servants. A letter written by ‘A Suffering Materfamilias’ in February 1874 to the editor of The Perth Gazette and Western Australian Times described what they were experiencing as “daily torture“.

They ended the letter with the following suggestion:

…let us put an end to the present state, and go in for at all events assisted female immigration, and thus remedy the evil from which families are now so sorely suffering…

Assisted immigration was established and advertisements (such as the two below) can be found peppered within the UK newspapers.

Elizabeth was one of the many British people who decided to take advantage of the free passage and, on 21 September 1877, at the tender age of 15, she departed England and emigrated to Western Australia on board the Robert Morrison.

It’s a curious decision for a 15 year old to make and, unfortunately, it’s not known what helped shape it. While it’s certainly possible she came across an advertisement such as those above, it doesn’t actually give any insight into why she chose to emigrate. Perhaps the family she was working for was emigrating and she was asked to join them (a strong possibility as this was mentioned by my Great Aunt). Maybe she was unhappy and desired a change. Or, perhaps a friend decided to  emigrate and encouraged Elizabeth to go with her. All manner of possibilities could be thought up in one’s imagination but I’ll likely never know what was the deciding factor.

emigrate and encouraged Elizabeth to go with her. All manner of possibilities could be thought up in one’s imagination but I’ll likely never know what was the deciding factor.

The Robert Morrison arrived in Fremantle on 20 December 1877 and, nine days before its arrival, a complete list of immigrants was printed in the paper (left). Elizabeth’s name has been highlighted in blue.

According to family legend, when Elizabeth arrived she knew her first name but only knew that her middle name started with the letter ‘M’. When writing out her name on documents, she picked the name ‘Maud’. It wasn’t until many years later when signing documents from England that she found she had to re-sign them. Elizabeth had signed ‘Maud’ but was advised by family that her middle name was actually ‘Mary’.

Elizabeth was one of eight single women on the ship who recorded their occupation as ‘domestic servant’. Along with Bridget O’Neil, she was also the youngest. Perhaps the older women, Ann Prior (35) and Martha Ann Daniels (32) took on motherly roles and mentored and cared for the younger passengers, most of whom were teenagers.

After having landed in Fremantle, Elizabeth would have then proceeded to Perth to the Immigrant Depot where she would await employment. Given how sought-after domestic servants were, it would seem she didn’t have to wait long. By early January 1878, The Inquirer and Commercial News reported that most of the immigrants who had arrived via the Robert Morrison had been snapped up by employers.

We are glad to learn that the majority of the immigrants by the Robert Morrison, who appear to be an unusually respectable lot, have met with employment at fairly remunerative wages.

For the next five years Elizabeth continued work as a domestic servant. The details of her life during this period (such as the families she worked for) are unknown but it’s likely she remained in the vicinity of Perth. She was also never mentioned in the newspapers so we can assume she kept out of serious trouble.

During this period domestic servants in Western Australia were still considered ‘in demand’ and many people regularly lamented the quality of those employed. It was also during this period that Sir Luke Leake prosecuted his two domestic servants for leaving his service without permission. They were sent to prison for 24 hours as punishment. The facts were later printed in The Herald when it became known that they had left his service because his wife, in a fit of anger, had told them to “take themselves off“.

The affair caused quite a sensation and resulted in discussion about the importance of servants and masters knowing their legal and moral obligations. It also caused frustration, with domestic servant, ‘Mary Jane’, writing a letter explaining the occasional difficulties domestic servants had in having to obey their masters. She ended with a description of what she had to endure.

Now, Sir, I have lived in several families with no experiences of this kind, but latterly I have known what it is on Sunday morning to be called four times up two flights of stairs, and be pelted with toilet paraphernalia while my mistress has been dressing for church, and when I objected to the missiles, to be laughed at and told that I had no witnesses, and to do my best…

Hopefully Elizabeth never experienced such behaviour during her employment.

It can also be assumed that in these five years Elizabeth settled in to her new life in Western Australia and began to make friends. She became associated with the Flynn family and family stories indicate she formed an acquaintance with Edwin Flynn who was the same age as her. It was through Edwin that she came to meet her future husband, William James Flynn.

On 6 August 1882 at St George’s Cathedral in Perth, Elizabeth (aged 20) and William (aged 26) were married. They initially made their home in Perth, before moving to York in the 1890s and then eventually back to Perth.

Elizabeth and William in 1932

She gave birth to eleven children between the years 1883 and 1908, all of whom were given her maiden name as their middle name; a common tradition during the Victorian era but one that I personally find inspiring. Such choices, even if common during the era, are not actually common on my family tree. I’m not sure if there was any meaning behind the decision but it indicates a woman with a strong sense of her own mind and a desire to acknowledge the family she’d left behind. Perhaps it also indicates the great deal of respect William had for her.

Elizabeth outlived her husband by 15 years. She even outlived three of her children. She was 89 years of age when she passed away in Subiaco on 30 May 1952.

With her death, much of the information about her life and her early years in England and Western Australia was gone; a fact that is quite common when it comes to researching female ancestors. Perhaps she told some stories to her children who then passed them along to their children but, as the generations grew, the stories stopped being recounted. I certainly grew up with barely any knowledge of Elizabeth and the life she lived.

Like so many women throughout history, much of her story is lost. She was a wife, a mother, a friend, a woman. Throughout her life she would have played a number of different parts and would have impacted many people in different ways. She could cook, she could clean, she was known as a skilled dressmaker, she cared for her family and she cared for her husband in later years when dementia set in. She was probably an interactive member of the communities she lived in. She was considered kind and intelligent. She was my 2nd Great Grandmother. I never knew her but I certainly admire the choices she made throughout her life, especially the brave choice to emigrate at age 15. In telling her story, I can’t delve into great detail about who she was and what she experienced but I tell it as best I can. She was a woman whose story was rendered invisible in the history of the world but I hope in telling it I’ve helped make it visible again.

Like so many women throughout history, much of her story is lost. She was a wife, a mother, a friend, a woman. Throughout her life she would have played a number of different parts and would have impacted many people in different ways. She could cook, she could clean, she was known as a skilled dressmaker, she cared for her family and she cared for her husband in later years when dementia set in. She was probably an interactive member of the communities she lived in. She was considered kind and intelligent. She was my 2nd Great Grandmother. I never knew her but I certainly admire the choices she made throughout her life, especially the brave choice to emigrate at age 15. In telling her story, I can’t delve into great detail about who she was and what she experienced but I tell it as best I can. She was a woman whose story was rendered invisible in the history of the world but I hope in telling it I’ve helped make it visible again.

Sources:

- Birth date and place of birth for Elizabeth Maud Holt courtesy of Audrey.

- Family stories courtesy of Aunty Betty.

- Photo of Elizabeth Flynn outside her house courtesy of Jo.

- Information relating to The Elementary Education Act of 1870 and the image of the children courtesy of Ancestry.com.au (http://www.ancestry.com.au/contextux/historicalinsights/elementary-education-act-1870/person/-276527416:1030:12093376).

- 1871 English Census courtesy of Ancestry (Class: RG10; Piece: 3220; Folio: 45; Page: 20; GSU roll: 839266).

- Warwickshire County Record Office; Warwick, England; Warwickshire Anglican Registers; Roll: Engl/2/1218; Document Reference: DR 380

- 1874 ‘FEMALE SERVANTS.’, The Perth Gazette and West Australian Times (WA : 1864 – 1874), 27 February, p. 3. , viewed 05 Mar 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3748953

- Leeds Times; 1 May 1875; Page 4. Obtained courtesy of Findmypast.

- Dewsbury Reporter; 13 January 1877; Page 5. Obtained courtesy of Findmypast.

- 1877 ‘LIST OF IMMIGRANTS PER “ROBERT MORRISON.”‘, The Western Australian Times (Perth, WA : 1874 – 1879), 11 December, p. 3. , viewed 05 Mar 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article2978470

- 1878 ‘NOTES FROM NORTHAMPTON.’, The Inquirer and Commercial News (Perth, WA : 1855 – 1901), 2 January, p. 3. , viewed 06 Mar 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article65956956

- 1879 ‘A SERVANT GIRL’S QUESTIONS?’, The Herald (Fremantle, WA : 1867 – 1886), 17 May, p. 3. , viewed 06 Mar 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article110470079

The story I was told as a little girl was that I was born in the darkness of night amidst a great and powerful storm. Rain fell down in sheets, thunder growled and grumbled and lightning struck so often that there was almost no need for a lamp in my parents’ small hut. My mother screamed with the weather and I resisted and then slid forth into the world, screaming along with her.

The story I was told as a little girl was that I was born in the darkness of night amidst a great and powerful storm. Rain fell down in sheets, thunder growled and grumbled and lightning struck so often that there was almost no need for a lamp in my parents’ small hut. My mother screamed with the weather and I resisted and then slid forth into the world, screaming along with her.

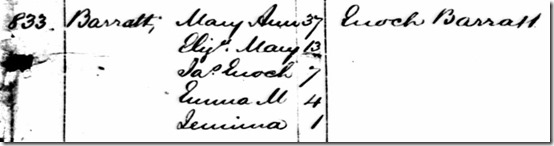

a departed England on board the Victory. The journey took about 90 days with the ship arriving in Fremantle on 24 March 1854. One can only imagine the euphoria felt by Enoch and Mary Ann when they finally saw each other after three years of being apart.

a departed England on board the Victory. The journey took about 90 days with the ship arriving in Fremantle on 24 March 1854. One can only imagine the euphoria felt by Enoch and Mary Ann when they finally saw each other after three years of being apart.