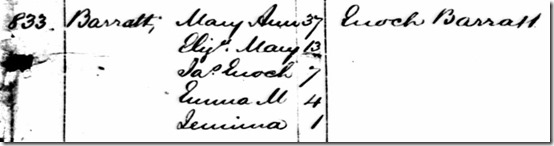

Last year I wrote a post in which I pondered, who was Jemima Barratt? Listed as an assisted passenger with Mary Ann, Elizabeth, James and Emma Barratt, she was an anomaly within the Barratt family history. Was her listing a mistake or, was there more to the story? The answer remained absent until I took a risk and ordered birth and death certificates from England’s General Register Office. The receipt of the certificates has since altered the known history of the Barratts and sheds more light on the plight of Mary Ann after her husband, Enoch, was first incarcerated and then transported to Western Australia.

The two Barretts were sentenced to 10 years’ transportation…

Having been found guilty of receiving stolen goods on 12 May 1851, Enoch Pearson Barratt and George Pearson Barratt (brothers) faced one of the most undesirable punishments of the Victorian era: transportation.

While details of the brother’s lives after their convictions are easily obtainable (both spent time in Newgate and then Wakefield Prisons) it is the lives of their families and how they fared which has often weighed on my mind. What did their wives do after their husbands were sent to prison?

Far from accepting the fate doled out to their husbands, Mary Ann (Enoch’s wife and my 4th Great Grandmother) and Mary (George’s wife) decided to fight for them; both submitting petitions pleading to those with power to prevent their husbands from being transported.

Both were illiterate. Both approached different people to help them write the petition. Both petitioned Sir George Grey who was Secretary of State for the Home Department. From Deptford, Mary Ann spoke of Enoch’s good character and, in proof of this, provided a certified copy of a letter he received from George Hawkins (a Manager of the London, Brighton & South Coast Railway) many years before. She went on to state that Enoch was innocent and that witnesses (who most likely supported Enoch’s story) were in attendance and were not called. Essentially, she put forward that there had been injustice in the Court.

The letter from George Hawkins. It seems likely the date (1837) on this letter is incorrect. Most records indicate Enoch was still in Newport Pagnell at this point in time. The year 1847 is a better fit though I can’t explain why it was recorded incorrectly.

Mary, writing from Newport Pagnell in Buckinghamshire, spoke of the nine children (all dependents) she would have to raise on her own and touched on the evidence of Sergeant Carpenter (the Policeman who uncovered the brothers’ scheme) stating that “Carpenters evidence against her husband was of a very questionable and unsatisfactory nature and was much commented on by the Counsel on the Tryal.“

Both gave compelling arguments but only one petition was successful. In the end, Mary’s letter won over the Secretary and George’s sentence was commuted. Unsuccessful, Mary Ann faced the reality that she would soon lose Enoch, not just to the prison system, but for good, as he was to be transported to a country on the other side of the world.

Mary Ann’s petition forms part of Findmypast’s Crime, Prison and Punishment documents (originally from the UK National Archives) and consists of seven pages. Unfortunately, due to an error, only page one is available on their website. Despite having advised them of the error many times since September last year, it has not been rectified. Unfortunately this blog post has been written without the knowledge of what the subsequent pages contain. Perhaps in the future (when the document is available in its entirety) I’ll be able to edit this post to include the extra information.

Enoch remained in prison (first Newgate before being transferred to Wakefield) for another year before he was transported to Western Australia. Mary Ann most likely went back to Deptford. Today (according to Google Maps) it’s a 20 minute drive from Deptford to the Old Bailey (the area where Newgate Prison once stood) and it takes over three hours to drive from Deptford to Wakefield (in West Yorkshire). Back in the 1850s these journeys would have been significantly longer. With three children and limited income, the thought of Mary Ann regularly visiting her husband in either prison is not one I entertain. Perhaps she was able to see him one last time but, it’s realistic that the last time she saw him was when he was standing in the dock at the Old Bailey.

What became of Mary Ann during this period is unknown. Resigned to her fate, she had to get on with her life as best as she could. Now the sole parent and provider of three children under the age of 12, she may have had to take on jobs to obtain a small income. If work was scarce, perhaps she fell back on the generosity of family members or benevolent societies.

Despite the fact that Enoch was still in England (albeit not as a free man) Mary Ann also did not abstain from interactions with the opposite sex. Sometime in February 1852 (nine months after Enoch’s conviction) she slept with a man by the name of John. She was still living in Deptford and the nature of this relationship and how long it endured will remain Mary Ann’s secret.

By May 1852, she knew she was pregnant. One can only speculate on the thoughts that would have continually bubbled through her mind. She was pregnant when she had three other children to support. The father of the child wasn’t her husband. Adding to her worries, another child meant another mouth to feed. Perhaps she also thought of Enoch. It’s not known if she had news of his whereabouts but, at this point in time, he was chained up on the ship William Jardine bound for Western Australia.

Of course we can never know the nature of her relationship with John but, contradicting the aforementioned negative thoughts, perhaps she was happy at the prospect of having another child.

Enoch arrived in Western Australia in August 1852; Mary Ann was six months into her pregnancy. Three months later, she gave birth to a baby girl.

Born on 23 November 1852 at 26 Giffin Street in St Paul’s Deptford, Mary Ann decided to name her daughter Jemima. She registered the birth on 4 January in the new year and signed her name with a cross. She was still living at the address on Giffin Street. The name and occupation of the father were also provided: John Barrett, mariner.

Initially, one might think that Mary Ann had become associated with another Barrett but, in my opinion, the Barrett surname attributed to John may well have been a decoy to try and hide the illegitimacy of her child. In the Victorian era, where image meant everything and illegitimacy was scandalous, it looked much nicer if the father’s surname on a child’s birth certificate matched your own. There would also be less questions.

Meanwhile, in Western Australia, Enoch was slowly settling in to his new life. It didn’t take him too long before he found out that convicts could apply for their families to join them in the Colony. A letter was sent on his behalf and, by April 1853, it arrived in England.

At a meeting of the Board of Governors and Directors of St Paul Deptford, Sergeant Carpenter (the same Policeman mentioned at the start of this post) attended and put forward an application on behalf of Mary Ann requesting assistance for the family to travel to Western Australia.

He (Sergeant Carpenter) had made this application, in hopes that if the Board had power to assist, it would confer a great benefit to the poor woman, who although not at present chargeable to the parish, had very limited means of support for herself and children.

The Board considered his application and declared they would do everything in their power to have it approved by the Poor Law Board (where the funds would come from). The outlay of several pounds for the Barratt family’s travel expenses was acknowledged to be more favourable than if they remained in England and approached the parish for support.

They also praised Sergeant Carpenter for the trouble he had taken to help better the condition of the family and I can’t help but agree with them. It’s interesting to look at the juxtaposition of the situation. Sergeant Carpenter was the means of their downfall (through carrying out his duties as a Policeman) but was not so unfeeling that he neglected them afterwards. Even after the conviction was obtained it would appear he continued to try and help in some way.

It’s not known if the Board granted the funds but, on 10 June 1853, the following letter was sent from ‘H Waddington’ to Mr Thomas Marchant, the Vestry Clerk of St Pauls Deptford and related to Enoch’s request.

I am directed by Viscount Palmerston to acknowle [acknowledge] the rect. [receipt] of yr. [your] lr. [letter] of the 8th Inst, requesting to be furnished with information regarding the Grant of an Assisted Passage to Western Australia to the Wife and Family of Enoch Pearson Barrett, a Convict under sentence of transportation in tht. [that] Colony; and I am to acqt. [acquaint] you that the subject of yr. [your] lr. [letter] relating to the Colonial Department, Lord Palmerston has caused the same to be forwarded thither for the consideration of the Duke of Newcastle whose decision thereon will be communicated to you in due course.

The Duke of Newcastle granted his request and it was likely that Mary Ann was soon made aware that she could join her husband in Western Australia.

At some point she had to provide the names of family members who would be taking advantage of the free passage to join Enoch. They were listed in age order; Mary Ann’s name at the top followed by Elizabeth, James, Emma and, lastly, Jemima.

Despite the fact that Jemima wasn’t Enoch’s child, Mary Ann was not willing to leave her daughter behind. She was going to take her with her. It would have been an interesting conversation once the family arrived in Western Australia. Perhaps she was simply planning on telling Enoch that she was his daughter. Or, perhaps she didn’t care what Enoch thought and he would have to accept her as his own despite the fact that she clearly couldn’t have been.

The family was given embarkation orders to travel on the ship Victory but, by the time the ship departed England, Jemima was no longer listed as a passenger.

On 11 October 1853 at 12 Stanhope Street in Deptford, Jemima (only eleven months old) passed away from convulsions (most likely the final symptom of an underlying illness). Mary Ann registered the death the next day, again signing her name with a cross. Interestingly, Thomas Marchant, the receiver of the earlier mentioned letter, was also the registrar who recorded the death.

Any grief felt by Mary Ann would likely have been pushed aside fairly quickly. There was always work to be done and she had to care for her three elder children. The date of their departure was also steadily approaching and Mary Ann may have had to make preparations for the journey.

Just over two months later, on 28 December 1853, Mary Ann, Elizabeth, James and Emm a departed England on board the Victory. The journey took about 90 days with the ship arriving in Fremantle on 24 March 1854. One can only imagine the euphoria felt by Enoch and Mary Ann when they finally saw each other after three years of being apart.

a departed England on board the Victory. The journey took about 90 days with the ship arriving in Fremantle on 24 March 1854. One can only imagine the euphoria felt by Enoch and Mary Ann when they finally saw each other after three years of being apart.

They would have had a lot to catch up on and a lot to discuss. Did Enoch know about baby Jemima? If not, did Mary Ann tell him? Or, did she decide to keep those three years of her life a secret?

The only known photo of Mary Ann Barratt (nee Fleming) is the one on the left. When I was younger I looked at the image of a proud Enoch and then compared it to Mary Ann’s sombre expression. There was something slightly pinched about it and I often wondered if she was mean. With the benefit of wisdom and the discovery of baby Jemima (which adds immensely to Mary Ann’s story) I no longer consider this description accurate. She was a woman, and like so many women of the past, her story is mostly lost. I have no idea what she was like but I now have an idea of her strength and determination and a little more knowledge of what she went through on her own before she finally joined her husband in Western Australia.

Sources:

- “CENTRAL CRIMINAL COURT.” Daily News [London, England] 15 May 1851: n.p. British Library Newspapers. Web. 26 Sept. 2016.

- England & Wales, Crime, Prisons & Punishment, 1770-1935 (Findmypast online); HO18; Home Office: Criminal Petitions: Series II; Piece Number: 310; George Pearson Barrett.

- Registers Of Prisoners In The County Prisons Of Wakefield; Findmypast (Series: HO23 – Piece: 15).

- Convicts to Australia; William Jardine (http://members.iinet.net.au/~perthdps/convicts/con-wa6.html).

- Certified Copy of Jemima Barratt’s Birth Certificate obtained from the General Register Office. England & Wales, FreeBMD Birth Index, 1837-1915; Registration Year: 1853; Registration District: Greenwich; Volume: 1d; Page: 483.

- Certified Copy of Jemima Barrett’s Death Certificate obtained from the General Register Office. England & Wales, FreeBMD Death Index: 1837-1915; Registration Year: 1853; Registration District: Greenwich; Volume: 1d; Page: 404.

- Kentish Mercury; 16 April 1853; Page 5. Obtained via Findmypast.

- Correspondence and Warrants; Findmypast (Series: HO13 – Piece: 102 – Folio: 265).

- SRO of Western Australia; Albany Passenger list of Assisted Emigrants showing names of emigrants and from which countries selected; Accession: 115; Roll: 214 (courtesy of Ancestry).

What a fantastic and in-depth account of your ancestor’s story. Well done you!

Thank you for your kind words, Alex. Glad you liked the post. 😊

Very much enjoyed your post. I have often wondered what happen to the wife’s of my three convicts (1816 – Carbis x2 & Bassett) but as yet not found anything. It is wonderful that you have found something particularly as you written it up so well and shared your findings. Thanks for sharing, you have inspired me to go back and have another look.

Thank you kerbent. And I’m so glad my post inspired you to search again for records relating to your ancestors. 😊

Thank you. What a great story of our ancestory.

Glad you liked it, Barry. 😊

Great story Jess. My gosh those women had a hard life back then, what strength of character they must have had, despite their lack of formal education. Thanks for sharing Mary Ann’s story, and for bringing little Jemima to life.

Thanks Katrina! I’m glad you enjoyed the story of Mary Ann and Jemima.

Katrina sumed it up perfectly. I was also thinking of what a hard time women had in that era…almost a forgotten addition to the men. However, to me, the most poignant part of the story was the description of Jemima’s short life… Many would have glossed over her, but you gave her her place in history. Thanks for yet another interesting post.

Thank you! Ever since seeing Jemima’s name on the passenger list I’ve wanted to find out who she was. I’m so glad I took a risk & bought the certificates. She’s finally been placed on the Barratt family tree where she belongs.

It is always great when you can put people together, nice to know where they belong.

I have included your blog in INTERESTING BLOGS in FRIDAY FOSSICKING at

http://thatmomentintime-crissouli.blogspot.com.au/2017/02/friday-fossicking-feb-10th-2017.html

Thanks, Chris

Thanks, Chris! 😊