Unless, like me, you’re slightly obsessed with vintage advertisements, you may find yourself dismissing ads as a source to further enhance the stories of your ancestors’ lives. While searching through pages of ads may at times be cumbersome, often the gains far outweigh the inconvenience.

So, what can you find by exploring advertising in relation to genealogy? In this blog post I share with you a variety of different ways I’ve utilised historical advertising in order to add depth to my ancestors’ stories.

Businesses

If your ancestor owned a business there’s a good chance that at some point in time they would have paid to advertise it in the local newspapers.

Enoch Pearson Barratt established the first nursery in Perth and continually advertised in the Western Australian newspapers. The ads varied throughout the years and have provided me with examples of the types of plants he sold as well as how the business progressed; from simply selling plants, to stocking seeds and eventually moving into floristry. From a larger perspective, such ads also contribute to the history of Western Australia as a whole; illustrating what plants the settlers could purchase at a particular point in time. This ad from 1875 shows the variety of fruit trees that were on offer at Enoch’s nursery.

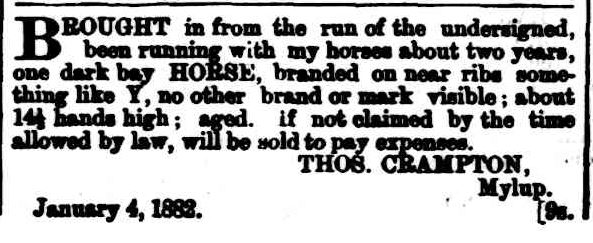

Farm Notices

Farm notices could relate to a variety of things but the ones I’ve commonly found concern animals wandering onto the farmer’s property or people trespassing on land. The notices are generally placed in the newspapers as a warning and, in the case of the animals, to give notice to the owner to come and collect them. Failure to collect the animal could result in the advertiser having the right to sell it to recuperate costs associated with caring for them.

These notices (which are often dated) allow you to place your ancestor at a particular location at a certain point in time. They also give insight into the types of issues which affected farming ancestors and how they went about overcoming them.

Employment

While initially this could mean simply searching for your ancestor to see if they placed an advertisement in ’employment wanted’ ads, more information could be obtained if you think broadly. After having ascertained through the Western Australian Government Railway Records that my Pop, Reece Nicholson, started working as a ‘Junior Worker’ on 17 July 1944, I turned to the historical advertising to see what would’ve been required of him when sending in an application. In no way does this ad mention my Pop’s name and while I have no way of knowing that this was how he find out about the job, the likelihood is that these were the requirements he had to fulfil.

Land

If your ancestors owned land, there’s a good chance you may find details in the advertisements relating to either the land they acquired or of its sale. Such ads enable you to pinpoint where your ancestor was living at a particular point in time or give greater insight into the properties they owned (especially if they owned several). These ads are also useful for the fact that they may give you greater details such as land locations (i.e. Wellington Location 48). This information could then lead you to broaden your research by obtaining land related documents such as Certificates of Title. The below advertisement from 1889 illustrates the type of information that may be obtained including specific details relating to the boundary of the property.

Announcements

Our ancestors did not have mediums such Facebook or Twitter to make various personal announcements to the world. They mostly relied on newspapers which, generally, were read by a majority of people. If you wanted to tell the world that you weren’t responsible for your spouse’s debts from a particular point in time, place an ad in the paper. If you wanted to thank a particular group of people, place an ad in the paper. If you wanted someone to make a public apology, induce them to place an ad in the paper.

The latter was the method my 2nd Great Grandmother, Edith Attwood (nee Theakston), decided to employ when faced with “false and defamatory slander” spread by Mrs F Elsegood. While finding historical advertising such as this is extremely interesting, it is also rather frustrating as it raises many other questions. How did she manage to convince her to place the ad? And what in the world was said?

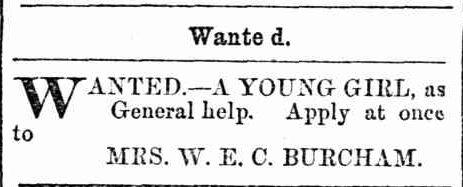

Wanted Notices

Wanted notices could relate to anything (boarders, particular items etc.) but the notices that I’ve come across in the course of researching my family history usually related to wanting to hire someone.

Finding your ancestor as an employer looking to hire particular staff (cooks, servants etc.) is often an indicator of wealth. There are not many within my family tree but during the height of the Barratt family’s business success, Maria Barratt (Enoch’s second wife) on occasion used the newspapers to find staff. Her ad for a “good cook” (below) can be seen sandwiched between two other similar ads.

If your ancestors weren’t wealthy enough to hire staff but you have the name of their employer, perhaps you could try to locate advertising which may have induced them to apply for a particular job (similar to what was mentioned previously under the heading ‘Employment’).

While transcribing the Hurst Farm Diary I came across an entry stating that Nellie Clifton Hurst had gone to Mrs Burcham. By searching for Mrs Burcham and using the advanced search function (narrowing down the results to around the date listed in the diary) I came across the following ‘Wanted’ notice. There is a good chance that this was the ad that Nellie saw when she decided to apply for the job.

Immigration Notices

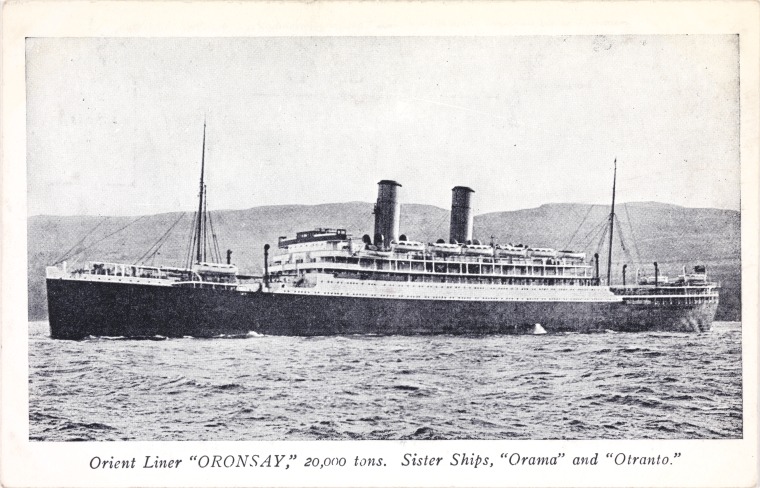

The arrival of immigrants in any State was often met with great enthusiasm and, in the early years, a list of names was often printed in the newspapers. These lists were generally found in the advertising section.

Not only can these lists give you the name of the ship your ancestor travelled on but they also give you an accurate date of their arrival as well as the possibility of finding other relatives. Look further afield and you may find connections with other passengers who weren’t related. The below passenger list for the ‘Strathallan’ lists my 3rd Great Grandfather, Patrick Grady, as well as his wife, children and siblings. Genealogical gold.

Think outside the box…

My last tip with regards to historical advertising and how it can be applied to genealogy is to think outside the box. By all means search for your ancestors’ full names but also try searching for their surname on its own, or their surname combined with the area they lived in. Perhaps try searching specifically for their address (i.e. “111 Hay Street”) or the name of the property they lived on. You may also wish to try searching for their occupation. You may not find anything relating to them, but similar ads can give you an indication of what they may have looked for in the papers.

Furthermore, utilise Trove search functions. Use the advanced search function to search between specific dates. If you’re searching using only a surname and would like to specifically find advertising relating to that name, try refining your results by clicking on the state where your ancestor lived and then click on ‘Advertising’. This will remove all newspaper articles so that you can concentrate only on historical advertising.

In this blog post I’ve provided you with seven examples of how historical advertising can help enhance your family history but I’m sure there’s many more that I’ve missed. If you have any other suggestions or would like to share how historical ads have helped you with your research, please feel free to leave a comment.

Happy searching!

Sources:

- 1875 ‘Advertising’, The Inquirer and Commercial News (Perth, WA : 1855 – 1901), 2 June, p. 2. , viewed 01 Sep 2016, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article65962599

- 1882 ‘Classified Advertising’, The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954), 20 January, p. 2. , viewed 02 Sep 2016, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article2986249

- 1889 ‘Advertising’, Southern Times (Bunbury, WA : 1888 – 1916), 18 June, p. 7. , viewed 10 Jan 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article164854148

- 1944 ‘Advertising’, Kalgoorlie Miner (WA : 1895 – 1950), 11 October, p. 3. , viewed 02 Sep 2016, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article94793401

- 1889 ‘Advertising’, Southern Times (Bunbury, WA : 1888 – 1916), 16 July, p. 4. , viewed 02 Sep 2016, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article164854295

- 1906 ‘Advertising’, The Daily News (Perth, WA : 1882 – 1950), 21 September, p. 6. , viewed 10 Jan 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article82457142

- 1886 ‘Advertising’, The Daily News (Perth, WA : 1882 – 1950), 28 August, p. 3. , viewed 10 Jan 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article76212367

- 1894 ‘Advertising’, Bunbury Herald (WA : 1892 – 1919), 21 February, p. 2. , viewed 10 Jan 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article87084606

- 1862 ‘Classified Advertising’, The Perth Gazette and Independent Journal of Politics and News (WA : 1848 – 1864), 7 February, p. 2. , viewed 10 Jan 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article2933675

Though perhaps surprised to see us, never were they annoyed by an unexpected visit. We all piled into the kitchen (which was also the dining area) and Grandma would start preparing; putting on the kettle for tea, digging out biscuits or cakes (which she nearly always had on hand) or creating a snack: Sao biscuits with butter, cheese and perhaps tomato or gherkin.

Though perhaps surprised to see us, never were they annoyed by an unexpected visit. We all piled into the kitchen (which was also the dining area) and Grandma would start preparing; putting on the kettle for tea, digging out biscuits or cakes (which she nearly always had on hand) or creating a snack: Sao biscuits with butter, cheese and perhaps tomato or gherkin.

Government Gazette (right) further helped to advertise the types of trades in which the men were proficient. Under the column ‘Married and with Families’, Charles would’ve been marked as a ‘bricklayer’ while Samuel marked as a ‘carpenter’.

Government Gazette (right) further helped to advertise the types of trades in which the men were proficient. Under the column ‘Married and with Families’, Charles would’ve been marked as a ‘bricklayer’ while Samuel marked as a ‘carpenter’. been in Geraldton for some time and over that time he’d purchased several lots within the town. Perhaps his debt became far too much for him. By 26 November 1862 everything he owned (including his carpenter’s and joiner’s tools which were vital for his work) was advertised for sale by auction.

been in Geraldton for some time and over that time he’d purchased several lots within the town. Perhaps his debt became far too much for him. By 26 November 1862 everything he owned (including his carpenter’s and joiner’s tools which were vital for his work) was advertised for sale by auction.